Tribe began as a musical ensemble in 1971 co-founded by Saxophonist Wendell Harrison and trombonist Phil Ranelin that soon expanded into a broad amalgam including a live collective and independent record label. Ignored by the mainstream, many African American jazz artists in Detroit and across the US began creating their own small imprints and Tribe emerged alongside other cultural entities to express selfdetermination goals in the city: saxophonist Ernie Rodgers with his sessions at Rapa House; John and Leni Sinclair’s Artist Workshop; Bruce Millan’s Repertory Theater; the Hastings Jazz Experience and the Strata Corporation led by Kenny Cox. Harrison’s ideas of independence, self-determination and education were central to the Tribe ethos: “I might be possessed with a drive to get the knowledge out,” explained Harrison, “because I see this as sustaining the future of the jazz diaspora, the jazz tradition.” Tribe album releases like Harrison’s ‘An Evening With The Devil’ (1972) and Harrison and Ranelin’s ‘A Message From The Tribe’ (1973) became early ‘70s milestones in Detroit jazz.

In 1977, Harrison teamed up with pianist/composer Harold McKinney to form Rebirth Inc., aided by Detroit cultural warrior John Sinclair, a continuation of the Tribe community ethos. Musically, it formed a link with radio station WDET and began an outreach program to teach children and to publish Harrison’s jazz instruction books. Harrison continue to record extensively as a leader with his own labels, WenHa and Tribe, documenting the collective through sessions led by Phil Ranelin, Harold McKinney, Pamela Wise and more.

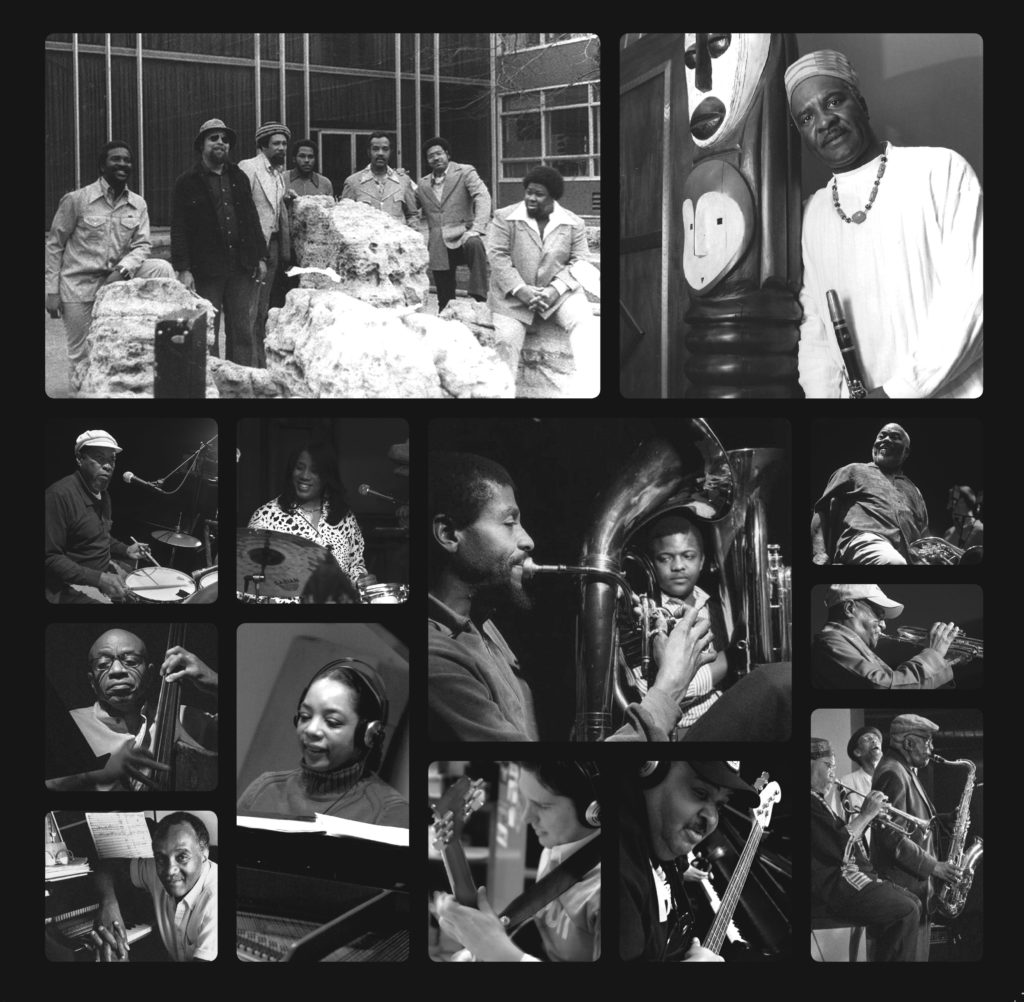

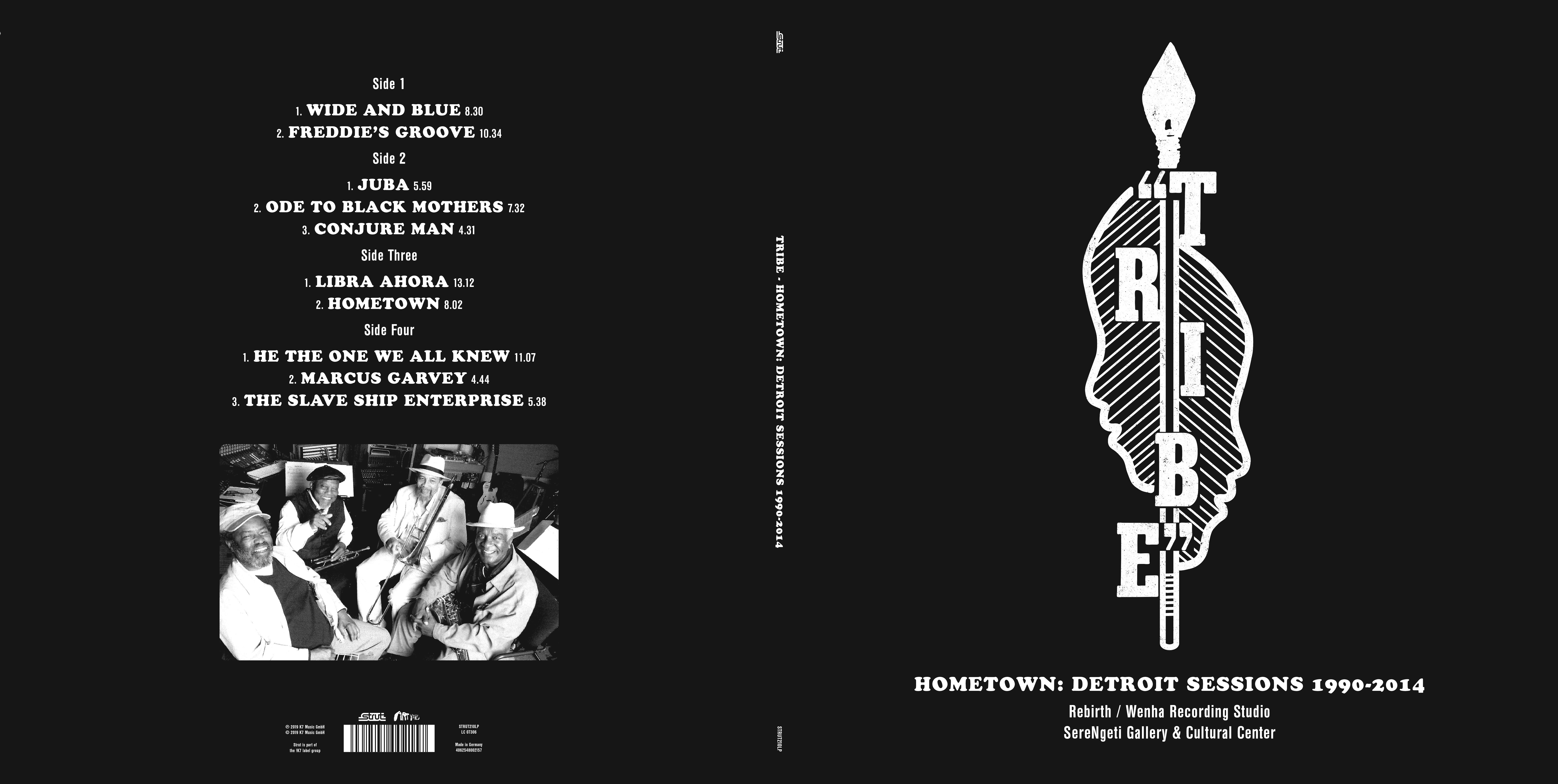

The ‘Hometown’ compilation places the spotlight on this later era of Tribe and Rebirth Inc., with rare and previously unreleased recordings from Harrison’s WenHa / Rebirth Studios and the SereNgeti Gallery And Cultural Center. Among many highlights, Harold McKinney and his “McKinfolk” family of musicians contribute the pulsing ‘Wide And Blue’ and dance celebration ‘Juba’; Phil Ranelin re-works his classic ‘He The One We All Knew’; Poet Mbiyu Chui (Williams Moore), pianist Pamela Wise and percussionist Djallo Djakate spark on the uncompromising ‘Ode To Black Mothers’ and the rallying cry of ‘Marcus Garvey’: “If we ever get together we will astound the world.” Harrison himself evokes the power and majesty of juju on ‘Conjure Man’.

‘Hometown’ comes as a 2LP gatefold and 1CD digipak fully remastered by Technology Works from the original session recordings. Both formats include exclusive sleeve notes by journalist Herb Boyd with rare photos from Wendell Harrison’s personal archive.

In 2018, Wendell Harrison was the recipient of the 10th Kresge Eminent Artist award, and propitiously the event took place at the Detroit Institute of Arts, where in 1971, Tribe, the musical collective Wendell co-founded, had its first major performance. “In the wake of the Tribe collective,” Rip Rapson, the President and CEO of the Kresge Foundation continued in his introduction at the affair, “Wendell created his own record label and a nonprofit organization to produce, present, record, distribute and teach young people in particular about this great musical tradition to which he belongs.” Rapson then provided slices of Wendell’s early years, including his student days at Northwestern High School and the later tutelage he received from the esteemed pianist/composer Barry Harris. “I still use what Barry taught me in my workshops and in my books,” Harrison has often noted. “Barry taught me music pedagogy; he taught me the tenets of improvisation, and basically, the language of jazz.” Those lessons were vital in his musical development and added to a jazz intuition that was further refined during a decade in New York City and a stint with Hank Crawford’s band. When Wendell returned to Detroit he already possessed ideas of independence and self-determination and it didn’t take too much convincing from him for me to join this visionary in both a cultural and entrepreneurial journey. When asked to explain his love and desire to achieve as a musician, Wendell said, “I might be possessed with a drive to get the knowledge out, because I see this as sustaining the future of the jazz diaspora, the jazz tradition,” he said during an interview by the editor of the Kresge monograph. His concept of Tribe began as a musical ensemble he founded with trombonist Phil Ranelin that soon expanded into a broad amalgam that included a business component, a record label primarily created to take Tribe’s music beyond the club and concert stage. It was an idea that was resonant in a period in which the African American community, and certainly its artists, were beginning to find alternatives to being shut out of the mainstream, no matter the industry or enterprise. In fact, Tribe emerged along with several other cultural and musical entities expressing self-determination goals. Countless number of highly conscious artists and musicians, as early as the mid-fifties, had begun to combine their resources by joining forces through co-operatives. There was Ernie Rodgers, the great saxophonist and teacher at Northwestern High School and his crew at Rapa House; James “Blood” Ulmer, Doug Hammond, Dave Durrah, Charles Eubanks, Billy McCoy, Patrick Lanier, Rod Williams who all often performed at the Artists Workshop where John and Leni Sinclair were at the helm of revolutionary thinkers. Bruce Millan’s Repertory Theater was another outlet that welcomed the more avant-garde musicians. Ed Nelson, Dedrick Glover and Miller Brisker had the Hastings Jazz Experience and, perhaps most notably, there were the members of the Strata Corporation with Kenny Cox, Charles Moore, Bud Spangler, Ron Brooks, Danny Spencer, Ron English, et al. When Wendell returned to Motown the city was bubbling with jazz reverberations. One of my favorite aggregations of the day was Griot Galaxy with Faruk Z. Bey, Sadiq Bey and the rest of the Bey family. Moreover, there were artistic eruptions on other fronts such as the literary activity afloat at Broadside Press, launched in 1965 by poet Dudley Randall with the purpose of providing a platform and outlet for aspiring black writers who were unable to secure notice from the major publishing houses. Randall understood, as Berry Gordy had envisioned several years earlier, that there was a crop of talented writers in the city—and ultimately across the nation—eager to have their works reviewed and, if worthy, published. Integral to Gordy and Randall’s perspectives was a burgeoning, relatively affluent African American community and possibly the bedrock of their commercial and artistic dreams. Wendell had a similar approach but mainly centered on getting wider exposure to local musicians. With Wendell’s inexhaustible energy and ideas arriving at warp speed, that early plan quickly morphed into something much larger and the collective grew exponentially within a short period of time. He gave me the responsibility of overseeing the magazine he conceived, giving me free rein to round up the writers, graphic artists and photographers while he took care of the business end of things with printing, advertisement and distribution. Basically, Tribe, a unique magazine evolved from handouts at concerts, promoted companies and other events in the city. It was forged under the banner of The Harrison Association, and was, in effect, a family endeavor. Wendell was the president and CEO, his wife at that time, Patricia, was the magazine’s graphic designer and she was principally responsible for the daily work routine at the office. Wendell’s mother, Ossalee Lockett, was also a vital cog in the operations, and none more important than soliciting the ads for the publication. The magazine was reasonably successful and it gave Wendell and his cohorts the exposure needed for reviews of their performances, live or recorded. Eventually, it reached beyond the musical realm into issues we deemed pertinent, and this meant getting involved in the city’s fast moving political scene, particularly with the election of Coleman Young as Detroit’s first African American mayor. In one of the issues we featured Mayor Young as the cover story. Given Wendell’s multi-faceted interests (as well as the challenges he faced finding advertisers) it became a matter of focus and it became increasingly difficult to keep the magazine going whilst at the same time leading an ensemble and dealing with business matters, to say nothing of the getting the band into a studio for a recording. Soon, the magazine was shut down and Wendell began devoting more time and energy to producing the records and securing performances for the group. By 1977, Tribe magazine was history but Wendell, ever the dreamer, ever the visionary, teamed up with pianist/ composer Harold McKinney and they forged Rebirth Inc. In several ways Rebirth, which was ably abetted by cultural warrior John Sinclair, was a redo of Tribe with its tentacles touching various sectors of the community.

There was an excursion into the media realm via a connection with the radio station WDET; educationally it began an outreach program to teach children and continued the publishing arm through Wendell’s music and jazz instruction books. He also became prolific once more in his compositions and productions: “Since establishing Rebirth Inc.,” the Kresge monograph recounted, “Harrison has recorded extensively as a leader with his own labels, WenHa and Tribe; his CD, It’s About Damn Time, produced by John Shetler and featuring guest vocals from Detroit’s funk maestro Amp Fiddler, was released on the Tribe label and distributed by Rebirth Inc in 2011; two CDs by Pamela Wise – 2015’s Kindred Spirits and 2017’s A New Message From The Tribe – were also released on the Tribe label.” Enter Strut Records. Strut, for the most part, picks up where Tribe and Rebirth left off. Listening to the recordings assembled here is like a flashback to those nights within earshot of the band in various venues around the city, from the Strata Concert Gallery to Cobb’s Corner to the SereNgeti Gallery And Cultural Center where some of the tracks here were recorded. Directed and curated by Bill Foster, the SereNgeti became an incubator for Detroit talent, displaying black art exhibits and hosting dance, concerts, workshops and lectures. Harold McKinney and his organization, McKinney Arts produced a series of jazz vocal workshops and concerts there during the ‘90s and this album features tracks from a 1995 concert. ‘Wide and Blue’ is a McKinfolk number, that is the McKinneys – Harold, piano; Kiane Zawadi, trombone and Gayelynn, drums – are at the fulcrum with extended family members Francisco Ali Mora on percussion, legendary bassist Reggie Workman and trumpeters Jimmy Owens and Marcus Belgrave filling the bill. Of course, there is also Wendell’s sax sailing along smoothly on Workman’s rhythmic pulse. Harold was always known for his swift arpeggios on either hand as well as that renowned linearity so common among Detroit pianists. Both his dexterity and expansive chords are in play, allowing Belgrave and Owens all the harmonic space they need to present their sizzling narratives. After a nice fanfare from the horn section, appropriately in keeping with the title ‘Freddie’s Groove’ we hit familiar terrain for Belgrave and Wendell, who, like a loving couple, know each other so well they can finish each other’s sentences, in this case the riffs and phrases inherent in the bop lexicon. A different kind of parlance erupts on ‘Ode To Black Mothers’ and the flow belongs to poet Mbiyu Chui (William Moore) and percussionists Mahindi Masai, Gregory Freeman, Akunda Hollis and brother Uche accentuating the words with beats that originate from across the African Diaspora. Pianist Pam Wise comps and deftly underscores Chui’s message, anticipating the rallying cry to his brothers and sisters that he delivers on ‘Marcus Garvey’: “If we ever get together we will astound the world.” On ‘Juba’, the McKinfolk are not only together, they can move effectively in a singular way as Harold gives the tune the proper bounce with spirited intervallic leaps at the keyboard as if mimicking a nimble dancer doing a version of the juba. Owens’ trumpet rides the upper regions of the tune, sketching marvelous tableaux of sound, and the villages of our mind come alive. Belgrave is no less a griot with a horn, telling tales like a returning troubadour ready to enlighten with tantalizing songs full of melody as he sets the stage for Zawadi’s trombone that brings the village into a quiet, meditative sunset. Providing additional gravitas and vocal symmetry is Harold’s wife Michelle and their twin daughters, Sienna and Jore. We can presume that ‘Libra Ahora’ is Spanish for ‘Freedom Now’ and this piece provides a field day for Mora, the percussionist, as he embarks on a veritable festival of ritmo, while Zawadi, without any chordal prodding or cues, has an open range to explore, thereby allowing him full freedom of expression. His clear intonation is just one of the gifts in his arsenal. Moreover, there are brilliant exchanges between him, Wendell and Owens. ‘Conjure Man’ belongs primarily to Wendell and his horn is the embodiment of juju, evoking all the power and majesty associated with the conjurer. Go back and savor again his performances on ‘Farewell to the Welfare’ and ‘Wait Broke the Wagon Down’ and you can hear how he steadily found ways to give his solos even deeper meaning. The spell he casts here is given a blues embroidery by Harold and Workman pushes the tonality to even lower depths, although the bottom seems endless. On a previous recording I expressed how much I enjoyed ‘Hometown’ and Pam and Wendell, a dauntless duo, are at the center of this track that exemplifies their fidelity to each other and their abiding love for Detroit. Practically every section of the city is evoked on this tune and you can follow them musically from old Black Bottom, up Cass Avenue past Wayne State University to the Bluebird Inn on the West Side, to Baker’s Keyboard Lounge near the city’s border. But it’s the mood they convey as they relax at home, his horn caressing her lush chords, that their mutual love and creativity exudes from the song. And John Douglas’s trumpet etches the sweet obbligatos, making the moment all the more blissful and enchanting. Trombonist Ranelin is the man on ‘He the One We All Knew’ and, as ever, he has a way of giving his wellrounded notes a sense of voice, his lines becoming almost verbal. They are very much like the deep resonance of his voice, and those of us old enough to recall his version of ‘Round Midnight’ can attest to the warmth he is capable of delivering. Bassist Ralphe Armstrong and drummer George Davidson are paired nicely as they devise a pleasant pulse for Ranelin to hang his phrases. ‘The Slave Ship Enterprise’ is exclusively Harold’s and from the first chord, from the first syllable, “The Baron” as he was affectionately called, owns the tune, blessing it with a light operatic touch and a recitative that only he could accomplish with a relish for language and the etymology of words. Like Ranelin’s interpretation of ‘Round Midnight’, Harold’s rendition of ‘Dolphin Dance’ with his added lyrics was unforgettable and I can still hear him at the piano, sometimes with Jhara, giving that Hancock composition a special turn. Harold joined the ancestors in 2001 at 72 but his music, particularly when combined with his partners in rhyme and rhythm – Belgrave, Wendell and the McKinfolk – is something we can cherish forever and on this recording the essence of his style and his genius is on full display. So too is the remarkable artistry of the late Marcus Belgrave who we lost in 2015, aged 78. He and Harold were instrumental in the founding of the Metro Arts Complex where they tutored hundreds of young aspiring musicians including Geri Allen, Kenny Garrett, and countless others. Like the McKinfolk, Marcus’ widow vocalist Joan Belgrave is committed to keeping the flame of Marcus’ life and work forever burning. And this album will be part of the everlasting impact both Harold and Marcus had on our culture, on our hope and possibilities. That same hope and aspirations pertain with Wendell and Pam and their luminosity is never more apparent than when they blend their formidable talents, whether on the bandstand or across the table discussing the next move of their partnership. Through Strut, Tribe and Rebirth have a fresh iteration, a way to move forward with integrity and with a vision that portends a most promising and sound future.

Herb Boyd, August 2019.

FREDDIE’S GROOVE 10.34

(Phil Ranelin) PhilRan Publishing (BMI)

HE THE ONE WE ALL KNEW 11.07

(Phil Ranelin) PhilRan Publishing (BMI)

Recorded live at Rebirth / WenHa Studios, Detroit, 1990

WIDE AND BLUE 8.30

(Harold McKinney) BeatStix Publishing (ASCAP)

JUBA 5.59

(Harold McKinney) BeatStix Publishing (ASCAP)

CONJURE MAN 4.31

(Harold McKinney) BeatStix Publishing (ASCAP)

LIBRA AHORA 13.12

(Kiane Zawadi) ENU Publishing (BMI)

THE SLAVE SHIP ENTERPRISE 5.38

(Harold McKinney) BeatStix Publishing (ASCAP)

Recorded at SereNgeti Gallery And Cultural Center, Detroit, 1995

PAMELA WISE

ODE TO BLACK MOTHERS 7.32

(Pamela Wise / Mbiyu Chui (William K. Moore)) Wenha Publishing (BMI)

HOMETOWN 8.02

(Pamela Wise) Wenha Publishing (BMI)

MARCUS GARVEY 4.44

(Pamela Wise / Mbiyu Chui (William K. Moore)) Wenha Publishing (BMI)

Produced by Wendell Harrison

Recorded at Rebirth / WenHa Recording Studio, Detroit, 2014

Personnel

PHIL RANELIN: Trombone (Tracks A2 and D1)

WENDELL HARRISON: Tenor Sax, Clarinet (Tracks A1, A2, B1, B3, C1 and C2)

MARCUS BELGRAVE: Trumpet (Tracks A1, A2, B1 and B3)

JIMMY OWENS: Trumpet (Tracks A1, B1, B3 and C1)

JOHN DOUGLAS: Trumpet (Track C2)

KIANI ZAWADI: Trombone, Euphonium (Tracks A1, B1, B3 and C1)

HAROLD McKINNEY: Piano, Vocals (Tracks A1, B1, B3, C1, D1 and D3)

PAMELA WISE: Piano (Tracks A2, B2, C2 and D2)

JOHN ARNOLD: Guitar (Track A2)

JACOB SCHWANDT: Guitar (Track C2)

RALPHE ARMSTRONG: Bass (Tracks A2 and D1)

REGGIE WORKMAN: Bass (Tracks A1, B1, B3 and C1)

GAYELYNN McKINNEY: Drums (Tracks A1, B1, B3 and C1)

GEORGE DAVIDSON: Drums (Tracks A2 and D1)

DJALLO DJAKATE: Drums (Tracks B2, C2 and D2)

FRANCISCO ALI MORA: Percussion (Tracks A1, B1, B3 and C1)

MAHINDI MASAI, GREGORY FREEMAN, AKUNDA HOLLIS, BROTHER

UCHE: Percussion (Tracks B2, C2 and D2)

MBIYU CHUI (WILLIAM MOORE): Poet (Tracks B2 and D2)

JHARA MICHELL McKINNEY (wife), SIENNA McKINNEY, JORE

McKINNEY (twin daughters): Vocals (Track B1)

Engineers: JIM GIBEAU, QUENTIN DENNARD II

All tracks licensed courtesy of Rebirth Inc. From the archives of WenHa Music / www.wendellharrison.com

Artist liaison and compilation by Peter Dennett, Art Yard Records

Liner notes by Herb Boyd. Herb Boyd’s ‘Black Detroit – A People’s History’ forthcoming from Amistad Press.

Graphic design by Matt Thame at Studio Auto / www.studioauto.co.uk

Photos reproduced courtesy of Riva Sayegh, Carl Craig, Barbara Barefield, Cybelle Codish and Patricia Harrison

Mastering and vinyl cut by Peter Beckmann at Technology Works / www.technologyworks.co.uk

Release co-ordination by Quinton Scott

Strut thanks: Wendell Harrison, Phil Ranelin, Pamela Wise, Peter Dennett, Duncan Brooker, Matt Thame, Peter Beckmann, Jim Johnstone, Manu Figueres, Tobi Kirsch, Jules Temple, all the distributors, Horst, Tom, Adrian, Zac, Siofra, Alice, Leigh, Karsten, Andrea, Monika, Sophie, Sina, Johanna, Adam, Lauren, Stas, Thomas, Denis, Aitor and all at !K7, Duncan Brooker, Juan Vandervoort, Payal Choudhary, Corey Scott, Laith Scott, Ananya & Aarav, original Strut – Toni, Tinku, Simon, Christine, Sean L

www.strut-records.com